Story of Coffee producing area | how can Ugandan coffee farmers save themselves in the face of many difficulties?

For professional baristas, please follow the coffee workshop (Wechat official account cafe_style)

Uganda ranks eighth in the world in coffee production, on a par with Peru and second in Africa after Ethiopia. Each year, Uganda typically produces 3 million to 4 million bags of 60-kilogram coffee, accounting for only 2-3% of global production, far less than big producers such as Brazil (55 million bags) or Vietnam (25 million bags). The main variety grown by Ugandan farmers is Robusta, which is of poor quality and is usually used for commercial mass production, such as Folgers coffee, rather than being sold to sophisticated coffee connoisseurs.

However, over the past century, coffee has been promoted to the most important and valuable industry in Uganda, worth more than US $400 million. Coffee accounts for 20% of Uganda's national export revenue, and the Ugandan Coffee Association (Uganda Coffee Federation) estimates that there are about 8 million Ugandans in 1 gamma, with most or all of their income coming from coffee. About 90% of the country's coffee is produced by small farmers.

President Yoweri Museveni (Yoweri Museveni), who has ruled Uganda since 1986 and portrayed himself as a farmer politician, calls coffee an "anti-poverty crop" (anti-poverty crop) and is trying to achieve an ambitious (which many local experts say impossible) goal of quintupling coffee production, or 20 million bags, by 2020. Uganda wants to have a place in the forecast that global coffee demand will double by 2050. This may solve long-standing social problems, in particular rural poverty and the food crisis affecting the population of 1 and 4, and a trade deficit of $3.3 billion (Uganda spends twice as much on importing oil as it earns from coffee).

But even without the effects of climate change, challenges remain. Farmers often lack access to basic tools such as fertilizers, irrigation and high-quality seeds, as well as services such as bank loans, agricultural training and market data, as well as infrastructure such as smooth roads and processing equipment. Most farmland is small, the larger ones are only smaller than football fields, and with the rapid growth of the rural population, the land is divided into smaller ones. The law cannot protect the land rights of small farmers, and the land will be seized by wealthy neighbors or foreign investors. Many young people would rather try their luck in Kampala than farm with their parents. Women often fall into weakness because the economic power of land and families is in the hands of men.

Overall, coffee cultivation in Uganda has not made much progress in the past century, and planting income has been stagnant at the worst level in Africa. So in today's global market, which focuses on mechanization and absolute quality standards, farmers are already at a disadvantage, compounded by the challenges of climate change.

Since the 1980s, the average annual temperature in Uganda has risen by 0.2 degrees Celsius every decade, in line with the global warming trend. It is estimated that the temperature rise will accelerate, and the temperature in Uganda may be 2 degrees higher than it is now in the middle of this century. Although the estimated total rainfall has not changed much and may even increase in some areas, the timing of rainfall is becoming increasingly difficult to grasp and is characterized by prolonged droughts interspersed with several torrential rains. An economic analysis commissioned by the government in 2015 predicts that due to climate change and the lack of response measures, coffee production in Uganda will halve by 2050, resulting in losses of up to $1.2 billion.

"the impact of climate change is deep and broad," said Joseph Nkandu, executive director of the Ugandan National Coffee Agriculture and farming Association (NUCAFE). If global warming continues, Enkandu says, the best seeds and farming methods in the world will not be enough to save his members.

"We are doing our best. But there are still insurmountable limitations. "he said.

The quality of coffee is assessed through a "cup test" process at Good African Coffee, a company in Kampala, Uganda. PHOTOGRAPH BY JONATHAN TORGOVNIK, GETTY IMAGES

Indomitable?

Winfrey Nakagawa (Winfred Nakyagaba) is fully committed to the work. She is a doctoral student in agronomy at the Pan-African non-profit Institute for the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture and is studying the effects of high temperatures and drought on coffee plants in central Uganda.

On a hot day in late January, she visited a small farm in Luwero. Luvero is the main coffee producing area, just north of Kampala. Usually, the rainy season is just over at this time of year, and the coffee trees are luxuriant and ready for harvest. But at the home of Gerald Joloba, a 47-year-old farmer who depends on three acres of farmland to support his wife and seven children, the leaves of the coffee tree are dry brown and break when touched.

When she found some coffee cherries (that is, coffee fruit containing coffee beans, so named for its bright red when it was ripe normally), it was hard and black. Nakagawa strode restlessly, picking up leaves and shaking his head. Everywhere she saw, there were needle holes left by the black bark beetle (twig borer), an invasive insect that thrives in warm, dry climates, withering or dying healthy coffee trees.

"if it had rained, there would have been coffee cherries hanging from these branches," she said. "now it's a pile of dead wood. "

"this rainy season is very bad," Holeba agreed. "it hasn't rained properly for four months. "

During the same period, Nakagawa also found the hottest temperature on record in Luvero. Holeba used his wallet to determine the extent of the impact. His harvest fell by 60%, while the annual income of coffee fell from the normal more than $800 to less than $300.

Most Luvero coffee farmers have a similar experience, although they are trying to cope with the drought in a variety of ways. They planted new coffee trees in the shade of banana trees to keep cool and reduce water evaporation; they dug holes around each tree to collect Rain Water; they spread compost made of leaves on the soil to maintain moisture; they buried water bottles poking holes next to each tree as a specially designed irrigation system. But the effect of these technologies is limited.

"they've done their best," Nakagawa said. "it's just really dry. "

Coffee's sensitivity to rainfall makes it "one of the worst crops for farmers in the face of climate change," said Peter Van Astian, an agronomist in Kampala at Olam International, one of the world's largest coffee dealers.

The demand for Rain Water is less, the speed of development and maturity is faster, and the newly developed special seeds which can resist diseases and insect pests can help farmers overcome the deteriorating environmental conditions. These improved seeds are widely used in places such as Brazil and Vietnam, but are rare in Uganda. They are expensive and require special planting techniques.

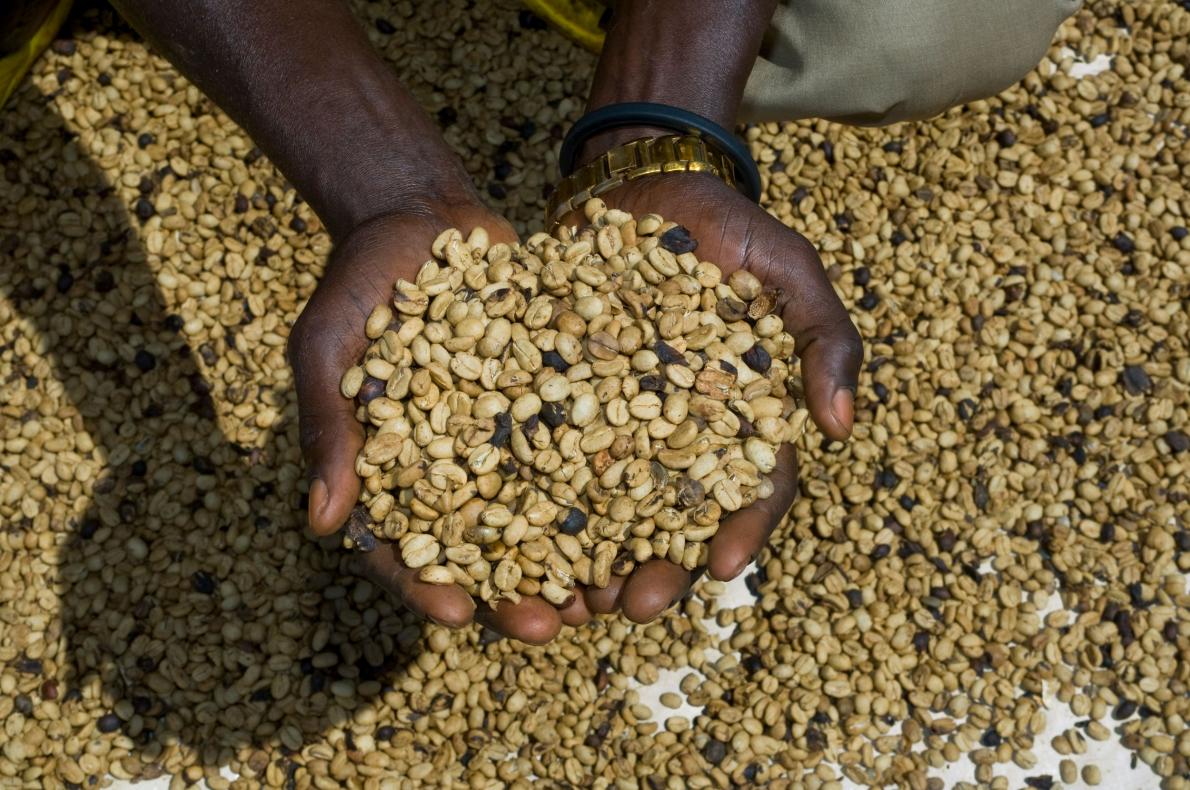

Freshly harvested unprocessed "green" coffee beans. PHOTOGRAPH FROM DESIGN PICS, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

Unite yourself.

That's why Ruth Ruth Magambo decided that farmers should help themselves.

Magambo is the president of Buki Naka, a group of women coffee farmers in Luvero. The name of Buki Naka is a mix of the names of several participating villages. Thirty members between the ages of 30 and 65 meet every week at the Magombo house to discuss how coffee and small farmers, especially women, work together to deal with most of the bad situations.

Throughout Uganda, coffee is seen as a "man's crop", meaning that husbands generally own land and coffee trees, as well as profits, even if it is mainly their wives who are working (and usually are). Members of Buki Naka are a few exceptions: some are widows who inherit coffee trees from their husbands, some earn enough money through small trade to buy a small piece of land of their own, and some husbands have advanced ideas and are willing to give coffee trees voluntarily.

In 2007, Buki Naka began to get together irregularly, sharing coffee-growing tips and gossip. But two years ago, Magambo said, members began to panic when deteriorating coffee production made it difficult for families to make ends meet. Therefore, they decided to seriously improve the industrial model. The first step is to start selling their coffee collectively in order to reduce costs and put them in a better bargaining position and negotiate a better price with the middle market.

"if we sell together, we can make more money," Magambo said. "because of the drought, the yield is low this season. However, we can make more money per kilogram (compared to separate sales). "

They have also set up an internal mechanism for the availability of loans. The fees paid by members plus interest, Magambo said, will increase the fund by up to $1400 a year, equivalent to the combined annual income of several families. The purpose of the loan includes improving farmland (such as seeds), paying family expenses such as tuition fees and cornmeal when coffee income is poor, and even buying land.

Several members said that when there was no loan available before, they had to steal some coffee from their husband's tree and sell it in cash to pay for daily use, just to avoid begging for accommodation. Now they have a way to be financially independent.

Bags of coffee beans are ready for export at the Kyagalanyi Coffee Ltd factory in Kampala. PHOTOGRAPH BY TREVOR SNAPP, BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES

When women have the right to manage farmland more directly, they can raise household income and adopt their own solutions to adapt to the climate, said Fortunette Fortunate Paska, a gender researcher in Uganda at the Hans Neumann Foundation (Hanns Neumann Foundation). On the contrary, "if you don't empower women, you will accomplish nothing because they are the ones who work in the fields." "

Members of Buki Naka are working to bring together men's groups to discuss matters related to managing the coffee industry to bridge the gender gap in Lovello.

"it's good for the development of the family," Magambo said. "because women play a paid role for men, men should see them benefit as well. "

Magambo's coffee is arriving at its first stop, a small shelling factory in a warehouse in downtown Luveiro. In the dark, the two-layer machine that put in the dried coffee cherries and kept spewing out a lot of shells made a deafening sound.

One of the workers asked me where I came from; when I said America, he pointed to a pile of coffee beans and replied, "one day those will come to your country." "but he is not sure what will happen when the coffee beans arrive at their destination.

"what do foreigners do with these coffee beans? "he asked, and the word" foreigner "is in East African.

"well, let's drink it. "I said.

"Yes, but other than that? "he said.

"actually, it's just for drinking," I replied.

He gave me an interesting expression, as if I had just made him confirm his absurd ideas about foreigners. He doesn't believe that the whole industry exists only to make a drink. When I asked him if he had had coffee, he smiled.

"We don't even have the money to buy Nescafe. "he said.

The dialogue illustrates one of the biggest obstacles to the growth of Uganda's coffee industry: Ugandans do not drink coffee. Ninety-five percent of Ugandan coffee is exported as unprocessed green beans, and the price required in the international market is much lower than processed coffee beans that can be directly ground. In the absence of a domestic market, all possible profits from baked beans and finished product marketing go to Europeans or Americans, not Ugandans. President Museveni recently described the situation as "modern slaves". But entrepreneurs like Gerald Katabazi (Gerald Katabazi) believe they have a way to change that.

In Uganda, most coffee farmers are small farmers who earn their annual cash income mainly by selling coffee beans. PHOTOGRAPH BY SVEN TORFINN, PANOS PICTURES

Can "enterprising Master" help make a difference in Ugandan coffee?

Among Uganda's few and closely connected baristas and coffee bakers, Katabazi is known as the "The Hustler", a nickname derived from his strong career ambition. He keeps moving, looking for coffee beans all over the country, or riding a boda-boda (passenger motorcycle) around Kampala to find partners and customers, trying to open up the domestic coffee market in Uganda.

Katabazi is the operator of Volcano Coffee (Volcano Coffee), a new coffee roaster that offers high-end ready-to-drink coffee for a variety of businesses and coffee shops near Kampala. As a child, he grew up in the countryside of southwestern Uganda, and his life always revolved around coffee. But like Luvero's question mark worker, he didn't know the ultimate use of coffee at the time.

It wasn't until his early 20s, when a family friend offered him a job as an office assistant at UCDA, the government agency that promotes coffee, that he realized how wide the coffee industry was. There, for the first time, he learned about the quality control that export markets desperately demand, as well as coffee roasting, and how to pull out a small cup of espresso espresso. He also tasted his first cup of non-Nestle instant coffee and fell in love with it. However, he was frustrated by what he saw at the exit.

"consumers in our country drink tea instead of coffee," he said. "We have not yet established a local market for baked beans. "

If Ugandans can process and drink more of their own coffee, he believes, it can create jobs and increase the value of coffee across the country. Through local baking and service, "I'm creating jobs as baking beans, baristas, operators," he says. "I'm adding value. "

Katabazi is not the only one who thinks so. NUCAFE, a lobby group, estimates that if Uganda roasted and packaged all raw coffee beans currently exported, annual exports could quadruple to $2 billion.

The important planning room for this emerging industry is located in a light beige warehouse on the outskirts of Kampala. The corridor inside is painted and sterilized, but the air is filled with a mouthwatering fragrance of freshly baked beans. A team of technicians bent over a stainless steel table and carefully classified the coffee beans according to their color and quality. Behind them is another technician partner who keeps looking through the window of the large black oven to see that the green coffee beans are roasted dark brown.

The place is affiliated with the University of Makerere (Makerere University) and is regarded as a common workspace for coffee entrepreneurs. Katabazi is here to sample a batch of coffee beans that he has just bought from a retailer called Mbale, a town at the foot of Mount Elgang. Coffee companies conduct "cupping" tests on the flavor of new crops for the first time, similar to the concept that the winemaker has just opened the barrel and poured out the first cup.

After the coffee beans of Katabazi are roasted and brewed more than a dozen cups of coffee, they begin to taste. We move clockwise around the table, fishing for each cup with spoons, sipping the mouth and turning our tongues, and then, like tasting wine, spit it out.

"We need to find the intensity of the fragrance," he said. "some strawberries, potatoes, and a little cream. It has a good aftertaste and low acidity. You only feel mild irritation on both sides of your tongue. "

Katabazi was satisfied and said he would call Mubarak's contact person to order more coffee beans. There is an urgent moral need to turn the country's coffee farmers into coffee drinkers, one cup at a time, he said. "We are bound to achieve great things in Africa in the future. "

There is no limit to the future of coffee

Can coffee bring such a bright future to Uganda? Despite the shortage of Rain Water, there is no lack of optimism.

The resilience of Ugandans can be seen in Judith Judith Otto. She lives in a rural area outside the town of Gulu in northern Uganda. It is barren land, deeply influenced by decades of terrorist rebellion waged by the Lord's Resistance Army (Lord's Resistance Army) and its famous leader, Joseph Kony.

For 20 years, the lives of Otu and his neighbors were affected by Kony's confrontation with government forces. According to Human Rights Watch (Human Rights Watch), when the Lord's Resistance Army finally withdrew from Uganda between 1987 and 2007, at least 20, 000 children were kidnapped, 1.9 million were displaced and tens of thousands of citizens were killed.

"the situation is so uneasy that sometimes we sleep in the bushes to hide. "said Otu.

One night in 2003, when the nightmare came, her 16-year-old son opened the door and found an armed member of the Lord's Resistance Army standing there. The man was silent, picked up his AK-47 automatic rifle and shot into the house, killing the boy and his 20-year-old brother standing near him. After Otu, her husband and four other children escaped from the house, the militants set fire to the house and farmland. The family ran away and did not return to the same place until 2015.

When they returned, they found that the house was gone and the farmland was covered with woods. But they began to rebuild, selling the cut branches as firewood in exchange for cash. Before the conflict, her husband planted coffee saplings given to him by some friends. She couldn't find it now, but when her husband heard about the government's sapling distribution plan, he decided to get some of it himself.

The guru's environment is not suitable for coffee growth. Farming conditions are even worse than those of Luvero, and even experts are not optimistic.

However, Otto and her husband succeeded in overcoming the difficulties and broke the expert's glasses. In just two years, they rebuilt their farmland and planted free saplings plus the saplings they bought and borrowed, totaling more than a thousand.

On the base of their burned house, they are using the income from coffee to build a larger modern concrete house with red doors and windows. Otu sat in front of the door, beside the yellow dog gasping, she looked at her lost land, her house is like a monument, announcing infinite possibilities.

"if we didn't have coffee, we wouldn't have this house," she said. "Coffee saved us. "

Written by: Tim McDonnell

Important Notice :

前街咖啡 FrontStreet Coffee has moved to new addredd:

FrontStreet Coffee Address: 315,Donghua East Road,GuangZhou

Tel:020 38364473

- Prev

Tea or coffee? Look at the changes in the history of British drinks, the struggle for supremacy of tea coffee!

Professional baristas Please pay attention to the Coffee Workshop (official Wechat account cafe_style) over the years, Britain's national image has been inseparable from tea. When most people think of England, they think of afternoon tea. However, this impression may be out of date, because after the new millennium, more and more British people have actually given up their quintessence tea.

- Next

Story of Coffee producing area | how can Ugandan coffee farmers save themselves in the face of many difficulties

For professional baristas, please follow the coffee workshop (Wechat official account cafe_style) Uganda ranks eighth in the world in coffee production, on a par with Peru and second in Africa after Ethiopia. Each year, Uganda usually produces 3 million to 4 million bags of 60 kg coffee, accounting for only 2-3% of global production, far less than Brazil (55 million bags) or Vietnam

Related

- How did the Salvadoran coffee industry develop in Central America?

- What exactly does the golden cup extraction of coffee mean?

- The Origin of Coffee flower

- [2023 Starbucks World Earth Day] there are more meaningful things besides free Starbucks coffee!

- What kind of coffee is there in Spain? 9 Flavors of Spanish Coffee

- Aromatic African coffee| Kenya's coffee culture and historical production area

- Liberica Coffee Bean knowledge: the characteristics of Liberian Coffee beans of the three original species of Coffee beans

- The origin and formula of Spanish latte introduces the taste characteristics of Bombon coffee in Valencia, Spain.

- How to adjust the solution of over-extracted coffee

- What is the tasting period of coffee beans? What is the period of coffee and beans? How should coffee wake up and raise beans?