Basic knowledge of how to change from grain to cup of coffee

Seattleites are curious. They want to know where their food comes from. We may know which breed of chicken we eat, or which farm the carrots we buy come from, or which beach the oysters we eat for dinner come from. Although Seattleites now prefer locally grown produce, one of their daily must-have drinks comes from the other side of the world. Few people know exactly how coffee beans grown in Africa, South America, or Central America, their nearest neighbor, are grown and processed. To that end, with the help of the Colombia Coffee Growers Association (FNC), I had the privilege of witnessing the entire process of coffee from a seed to a sapling to our cup.

At first, I was skeptical about this trip. Colombia has long been known for producing high-quality specialty coffee. But there was a time when coffee in Colombia was questioned. I noticed that not all beans from Huila were selected by Slate Coffee Roasters. Robin Pollard, a microbatch roaster at Vashon's Pollard Coffee, also admits that she wasn't a fan of Biya when she first started roasting coffee five years ago. But now she prides herself on the quality of her Colombia coffee.

With these questions in mind, I started my coffee journey. I wanted to meet Colombia's coffee hero, Juan Valdez. Although I eventually realized that Valdez was not a real person, I met Don Arilio Rios, the owner of the award-winning Fina La Descansa plantation. Don Arilio and his wife entertained me warmly and invited me to dine on their plantation. It's not easy to get to their plantations. You have to fly several hours from Bogota, the capital of Colombia, and then transfer to a bus to get there. Like other Colombia coffee growers, Don Arilio's plantation is only a few hectares. There are 550,000 coffee plantations in Colombia, each with an average area of only 4 hectares. Almost all plantations sell coffee through the Colombia Coffee Growers Association (FNC). Don Arilio's plantation was once part of his grandfather's plantation. As generations passed, the plantation grew smaller and smaller. Among his siblings, Don Arilio is the only surviving coffee grower.

Don Arilio first showed me how coffee grows. His saplings are disease-resistant trees specially selected by the FNC Society's research arm based on local soil and climate characteristics. He also said that the FNC Association's research branch is funded entirely by export tariffs on coffee. Coffee seeds are buried in a nursery box. The soil in the incubator came from a nearby riverbed. After a few weeks, Don Arilio would move a quarter of the seeds, the fully germinated saplings, into individual bags ready for planting. The distance between trees depends on the altitude of the planting site. After 18 months of vigorous growth, coffee trees begin to bear attractive coffee fruit. Every five years, growers prune coffee trees. Each coffee tree needs at most three prunes, meaning the plant lives for about 15 years.

After that, we had a quick tour of the entire plantation. There are no ladders on the plantation. The coffee fruit can be picked by the picker at any time. There was only one picker here. He always carries a radio with him and a small bag around his neck. Elsewhere, plantations often need more helpers during harvest season. But pickers are often mobile, and with so many crops to pick across the country, finding enough people is difficult. The picker was extremely fast. He could pick out the reddest and purest fruits from the colorful fruits in a few moves. As he explained to me how to pick and harvest fully ripe coffee fruits, he continued to pick them at an unslowing rate. At the end of the day, he would give the coffee fruit in his pocket to the owner in exchange for money. Wages are calculated according to the kilos of fruit and the proportion of fully ripe fruit.

Don Arilio chose to process the fresh-picked fruit on his plantation. You can overlook the exquisite green bean processing workshop from the top of the hill. The fruit falls down a pipe in the roof into a Rube Goldberg-esque desizer. The vibrations of the machine separate the peel and pulp from the beans. The beans then go into a washing machine. The washing machine cleans the residual mucous membrane on the surface of the raw beans. This process requires a long fermentation period. Eventually, the green beans fall into a tank, where they can be washed and sorted manually.

The last step before the green beans leave the factory is drying. Green beans are spread evenly in a greenhouse-like drying shed. This process is extremely important. Green beans must be completely and evenly dried to achieve the highest quality. Drying usually takes 5 days. Until the color of the green beans is up to par, they are bagged and shipped to local centralized processing plants for sale.

I followed the grower to the treatment plant. The bags of green beans are removed from the parchment (a dry film on the surface of the beans), sorted and graded according to quality. Don Arilio told me about a time when he thought his coffee was selling for too little, so he shipped it all back to the plantation and waited until the price reached its expected value before selling it here. Due to the excellent quality of his beans, his coffee sells for the highest price here, and the coffee is also rated as Premium coffees. You know, Colombia specialty coffee is popular in the American coffee roaster community.

Coffee growers like Don Arilio spend a lot of energy, time and money cultivating the best quality coffee. That's why Colombia's high-quality specialty coffee is enjoying a renaissance in the U.S. market. Geoff Watts, deputy general manager of Chicago Intelligentsia Cafe, once called Colombia "one of the best places in the world to produce coffee." Robin Pollard once said,"I always encourage people I meet to learn about coffee's origins and to realize that coffee, like wine, is fermented, roasted, and brewed in a way that greatly affects its final taste." She hopes coffee lovers in Seattle and around the world will "read more books and blogs about coffee." If you think my experience makes you fascinated, then you have stepped into your coffee hall.

Important Notice :

前街咖啡 FrontStreet Coffee has moved to new addredd:

FrontStreet Coffee Address: 315,Donghua East Road,GuangZhou

Tel:020 38364473

- Prev

Are you still obsessed with coffee grease? Crema of espresso

Many friends who use coffee utensils other than Italian machines always struggle with the fact that the coffee they make is free of oil. If we want to talk about this problem, let's look at it from two aspects. First, let's take a look at what's in a cup of black coffee besides water: caramelized sugars, flavored oils, quinic acid, and caffeine. If there is no flavor oil in the coffee, then stir-fry the coffee and stir-fry

- Next

Analysis and summary of coffee characteristics from different origins

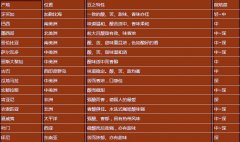

Jamaica Caribbean consistent sour, bitter, sweet, aroma is also good light ~ Central Brazil South America taste mild, sour bitter moderate, aroma soft Central Mexico North America grain large and sour strong, fragrant medium ~ deep Colombia South America sour, bitter, sweet heavy and thick, color as a good wine medium ~ deep Salvador Central America sour, bitter, sweet moderate ~ deep brother

Related

- Beginners will see the "Coffee pull flower" guide!

- What is the difference between ice blog purified milk and ordinary milk coffee?

- Why is the Philippines the largest producer of crops in Liberia?

- For coffee extraction, should the fine powder be retained?

- How does extracted espresso fill pressed powder? How much strength does it take to press the powder?

- How to make jasmine cold extract coffee? Is the jasmine + latte good?

- Will this little toy really make the coffee taste better? How does Lily Drip affect coffee extraction?

- Will the action of slapping the filter cup also affect coffee extraction?

- What's the difference between powder-to-water ratio and powder-to-liquid ratio?

- What is the Ethiopian local species? What does it have to do with Heirloom native species?