News of Brazilian coffee; rediscovered the legacy of Brazilian coffee tycoons.

About Archives

This is a digital version of an article in the Times print archives before online publication began in 1996. To keep these articles from appearing in the first place, the Times will not change, edit or update them.

Occasionally the digitization process introduces transcriptional errors or other problems.

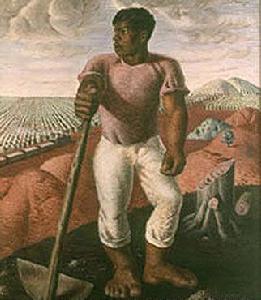

Brazil's architectural features consist of its Portuguese-influenced Baroque church, Oscar Niemeyer's modernism and the high-rise beaches of Rio de Janeiro. But now, cafes or coffee plantations that used to be the site of a powerful, slave-controlled rural aristocracy and Brazil's largest source of export are being rediscovered and are newly being rediscovered as an important part of the country's architectural heritage.

Now, built in the 19th century as a large, self-sufficient agricultural complex, it has become a status symbol for a new generation of wealthy gentleman farmers who replace coffee with purebred Arabian horses and prize cattle. But not just a beautiful country house, fazenda has become a new interest in Brazilian culture and history.

Unlike the pre-war south, the Brazilian plantation era transformed small-scale agriculture into large agribusinesses, rapidly creating a rich and complex new social class.

"I'll compare it with our coffee society," says Fernando Tasso Fragoso Pires, who has written several books on the subject, including Fazendas: big houses and plantations in Brazil, published in the United States last fall. (Abbeville Press). "Architecture is different, but they all believe that economic glory, as well as slavery, will last forever."

The plantations are concentrated in Vale do Paraiba, a lush valley in southeastern Brazil, slightly larger than long Island. The landscape has not changed much since the coffee trade broke out in the 1830s. The South Paraiba River is dotted with about 100 fazendas, winding through the states of Minas Gerais, Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Tropical vegetation, some of the densest in the world, suffocates tree trunks and branches and encroaches on unpaved roads. Royal palms, five stories high, pass through wavy leaves like a periscope. Here and there, opposite to the green tapestry, two-story French neoclassical mansions are being imposed, each with a typical plane, a symmetrical facade and a stone double staircase leading to the front door. But unlike most traditional maisons, these may have ochre walls in contrast to bright blue window frames, with coconut trees and pink hibiscus flowers in the garden.

A simple combination of tropical fashion and Old World refinement represents these country estates, attracting residents such as Roberto Marinho, the owner of Globo, a Brazilian media group, or Sergio Fadel, an art collector. But buying fazenda is not the place to start relaxing; it's the beginning of a difficult revival of the Odyssey.

"in Brazil, Trunda's situation is very special," said Isabel Rocha, an architect and professor at the Barra do Pirai Institute of Architecture in Rio de Janeiro. "Conservation is not part of culture, nor is it part of the economy or tourism. It is a luxury. "

Until recently, only famous baroque landmarks have been preserved, but now dozens of plantations have been faithfully restored and renovated, changing the architectural landscape of the area.

In 1816, the main neoclassical style of the manor arrived in Rio de Janeiro directly from France with architect Grandjean de Montigny, but little was known about local architects. Although the lines and proportions of the fazenda are in line with neoclassicism, the functions and indigenous building materials are new, so inventions and some kind of eclecticism are common.

The need for large areas of washing and drying of coffee beans led to the development of the quadrilateral project, with warehouses, granaries and slave dormitories on three sides of the terreiro (dirt courtyard). The fourth is occupied by the plantation owner's residence and its chapel, rising slightly so that slaves and fields can be clearly seen.

Many great houses have two floors, with rows of windows arranged symmetrically. There is little decoration, mainly for doors and styling cabinetwork, thus reflecting the influence of the colony rather than the purer neoclassicism found in France. For example, Bonsucesso, a site in the state of Rio de Janeiro, combines formal symmetry with a tightening of detail rooted in simpler buildings.

Compared with plantations in the southern United States, the wide porches, huge columns and Greek revival gables of Brazilian houses look lighter and more refined, with mixed elements such as country doors and imported porcelain and tapestries.

"the interior is decorated with bright colors-lots of red, gold and maroon," explains Rogerio Vianna, the owner of Santo Antonio do Paiol, a story from Valencia in Rio de Janeiro. "Green is very popular abroad, but here, there is green everywhere and we are tired of it."

SANTO ANTONIO DO PAIOL was founded in 1852 and underwent three years of painstaking restoration. The one-story house has a typical full-story basement, so it looks like two stories. The appearance color is influenced by Portuguese architecture: White walls, blue window frames, green blinds and yellow corners.

The house, sparsely furnished with 19th-century works, was found in a wine cellar and carefully restored. These include a sugarcane dining chair with a blue flower, a rare hardwood, an imperial-style bed, lion legs, and paintings by the original owner, the Estevez family.

Other plantations are also full of important antiques. It is hoped that the history of the San Martin plantation dates back to 1842 and includes a rare Brazilian plate and Antonio Lisboa's painted wooden altar, known as Alijadino, Brazil's most important baroque architect and sculptor.

In contrast, in Vargem Grande, contemporary gardens were designed by landscape architect Roberto Boehler Marx in 1970, and its commission includes gardens in the capital Brasilia and plans for Busquin Avenue in Miami. In Vargem Grande, luxuriant native plants are domesticated into square and rectangular patterns.

The architecture of fazenda has been rediscovered, revealing the attitude of plantation society towards style, luxury and nature. Coffee tycoons are eager to keep their distance from the surrounding wilderness; the less furniture and decorations they have, the better.

"for example, the interesting thing at the time was not just to repair wood, but to turn it into works of art," Ms. Rocha explained. "imagine that in a house, someone drew a pinho de riga grain pattern on real pinho de riga wood because it was an aesthetic appreciation."

With the demise of the coffee aristocracy brought about by the depletion of land and the liberation of slaves in 1888, the plantation was abandoned. Over the past 40 years, people have begun to buy and restore these great houses, but it was not until last year that these new owners United. Preservale is a non-profit organization that encourages the protection of fazendas and now has 60 members. Vianna, head of the group, said Preservale plans to guide some plantations and fund-raising activities.

"in France or Germany, castles are open to tourists and are part of the local culture," Mr. Pires added. "similarly, fazendas is an important part of our national heritage. The farm is our Loire valley. "

Important Notice :

前街咖啡 FrontStreet Coffee has moved to new addredd:

FrontStreet Coffee Address: 315,Donghua East Road,GuangZhou

Tel:020 38364473

- Prev

What is the difference between iced coffee and cold coffee? Cold coffee or iced coffee?

Information Please pay attention to coffee workshop (Weixin Official Accounts cafe_style) What is the difference between cold coffee and iced coffee? First of all, the concept needs to be analyzed clearly, that is, whether it is cold coffee? Iced coffee? Or traditional hot extraction after iced coffee, strictly speaking, this should belong to the category of iced coffee, therefore,[iced coffee] should be these finished coffee

- Next

What do you know about Japanese hand punching? Talk about the major genres of Japanese hand-made coffee.

Information please pay attention to the coffee workshop (Wechat official account cafe_style) on hand brewing, Europe and the United States is relatively bold, Japanese brewing is currently relatively popular in China, the general technique, pay attention to the forearm driven by the forearm, slowly turn around, keep the wrist motionless, control the size of the water always unchanged, but there are also sub-follicle type and trickling type, Japanese hand coffee has N methods and calls. Japanese style

Related

- Beginners will see the "Coffee pull flower" guide!

- What is the difference between ice blog purified milk and ordinary milk coffee?

- Why is the Philippines the largest producer of crops in Liberia?

- For coffee extraction, should the fine powder be retained?

- How does extracted espresso fill pressed powder? How much strength does it take to press the powder?

- How to make jasmine cold extract coffee? Is the jasmine + latte good?

- Will this little toy really make the coffee taste better? How does Lily Drip affect coffee extraction?

- Will the action of slapping the filter cup also affect coffee extraction?

- What's the difference between powder-to-water ratio and powder-to-liquid ratio?

- What is the Ethiopian local species? What does it have to do with Heirloom native species?